These enduring foundations of the United States of America have ties to the institution of slavery

10 Institutions You Didn’t Know Had Ties to Slavery

Yale University

One of the most respected higher-learning institutions in the United States, Yale University was named for American-born Englishman Elihu Yale (1649–1721). Yale was a governor and president of the East India Company, which was directly involved in the trafficking of enslaved people. Yale made his first donation in 1813, and in 1845 the college was officially renamed Yale University.

The school has made moves to right, if not rewrite, its history. In 2017, after much resistance, Yale’s undergraduate Calhoun College, which was originally named for John C. Calhoun, a 19th-century politician and slavery supporter, was renamed Hopper College in honor of Grace Murray Hopper, a Yale alumnus who became a leading computer scientist. In 2020, Yale launched the Yale and Slavery Research Project, and in 2024 it published the findings and issued a formal apology for its early leaders’ involvement in the slave trade.

The U.S. presidency

Forty-five men have been president of the United States, and 12 of them—more than a quarter—owned slaves at some point in their lives. Ulysses S. Grant, the 18th president, who served between 1869 and 1877, was the last one; the future Union general freed Williams Jones in 1859, two years before the war began. Today, activists are pushing to topple statues honoring slave-owning presidents like Grant, but not all critics of controversial monuments see it in such black-and-white terms.

“We put up their statues not to commemorate their slaveholding but for different reasons,” Manisha Sinha, professor of American history at the University of Connecticut, told NPR in June 2020. “So these statues, I think, need to be contextualized historically. We shouldn’t shy from the fact that many of these men were slave owners, but we should also be able to judge each case individually. The Confederate statues have no redeeming qualities to them, but other statues certainly do.”

The White House

“I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves,” First Lady Michelle Obama said during her speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2012, laying bare a shameful truth about the most sacred home in the United States. Indeed, the labor force that began construction of the White House in 1792 was made up largely of slaves, who were loaned out by their masters. And according to Jesse J. Holland’s book Black Men Built the Capitol: Discovering African-American History, once they finished toiling on the White House, many slaves went on to toil in it as well.

“Starting with Jefferson’s administration, the majority of the White House staff from 1800 through the Civil War consisted of slaves,” Holland wrote. “These slaves went with the U.S. presidents to work in the White House, because at that time Congress did not provide money for a domestic staff for the president.” Presidents who brought enslaved people to the White House include Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Andrew Jackson, John Tyler, James Polk and Zachary Taylor.

The U.S. Capitol

How’s this for some American irony? The building where, in 1865, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery was built more than a half-century earlier using slave labor. According to the Architect of the Capitol (AOC), the entity responsible for maintaining the landmark buildings and grounds of Capitol Hill: “Skilled labor was hard to find or attract to the fledgling city. Enslaved laborers, who were rented from their owners, were involved in almost every stage of construction.”

It’s impossible to determine the ratio of slave to paid labor, as enslaved people “were likely involved in all aspects of construction, including carpentry, masonry, carting, rafting, plastering, glazing and painting … And slaves appear to have shouldered alone the grueling work of sawing logs and stones,” as journalist Alexander Lane wrote in an article for the Poynter Institute’s PolitiFact in 2009. Lane cited a directive the building’s commissioners sent to quarry operator William O’Neale in 1794: “Keep the yearly hirelings at work from sunrise to sunset—particularly the Negroes.” Naturally, the owners pocketed most of the payments for the enslaved persons’ work.

The banking industry

The next time you make a bank deposit, consider this: You might be doing business with a financial institution that exists today because the bank and/or its predecessor banks benefited from slavery economics. In 2005, JPMorgan Chase & Co., stylized as JPMorganChase, apologized for the involvement two of its subsidiaries had in the slave trade. During the 19th century, subsidiaries Citizens Bank and Canal Bank in Louisiana accepted slaves as collateral for loans to plantation owners in the South.

“We apologize to the African-American community, particularly those who are descendants of slaves, and to the rest of the American public for the role that Citizens Bank and Canal Bank played,” read a letter signed by former JPMorganChase chairman and CEO William B. Harrison, Jr., and current chairman and CEO James Dimon. “The slavery era was a tragic time in U.S. history and in our company’s history.” The company also set up a $5 million scholarship fund for Black undergraduates in Louisiana. Other banking organizations, including Bank of America and Citibank, have been cited for historic ties to slavery, and Truist and Wachovia (before it was acquired by Wells Fargo in 2008) have apologized.

American whiskey

Beloved whiskey icon Jack Daniel’s may not have benefited directly from the slave trade, but it might not exist without it. According to whiskey lore, Jack Daniel learned how to make whiskey from a white distiller and preacher named Dan Call, but that’s the whitewashed version. During the 1800s, whiskey was largely made by Black Americans, and Call actually instructed one of his slaves, Nathan “Nearest” Green, to teach young Jack Daniel everything he knew about making whiskey.

Jack Daniel’s isn’t the only brand with a slavery-tainted past, but it’s one of the most prominent. Black people contributed greatly to the evolution of American whiskey, and while Jack Daniel’s acknowledged its past in 2016, most of the distilling experts have been lost to history. “It’s extremely sad that these slave distillers will never get the credit they deserve,” Fred Minnick, author of Bourbon Curious: A Simple Tasting Guide for the Savvy Drinker, told the New York Times in 2016. “We likely won’t ever even know their names.”

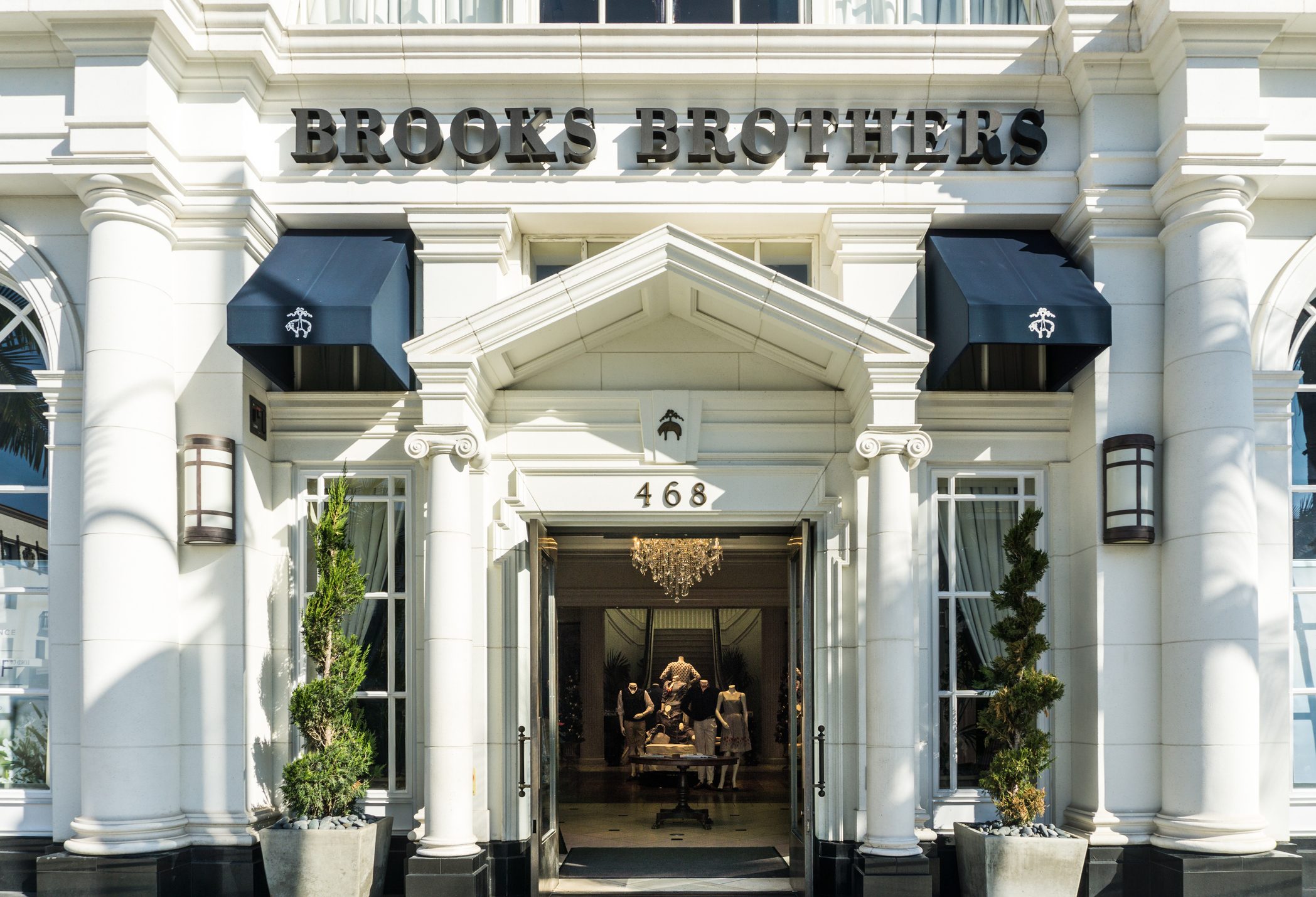

Brooks Brothers

During the pre-Civil War era, the American clothing company founded in 1818 regularly produced clothing that slave owners bought for slaves. “Brooks Brothers was top-of-the-line slave clothing,” Erin Greenwald, a curator at the Historic New Orleans Collection museum, told Smithsonian magazine in 2015. “Slave traders would issue new clothes for people they had to sell, but they were usually cheaper.”

Although other retailers sold slavewear, and Brooks Brothers was more than just a slave outfitter (Abraham Lincoln wore a Brooks Brothers custom-made great coat to Ford’s Theatre on the night he was assassinated in 1865), Brooks Brothers stands out as one of the few that survives to this day. It still hasn’t fully acknowledged its slavery ties.

U.S. currency

Currency often honors some of the most admired people in a nation’s history. In the United States, some of the men on our money also owned slaves: George Washington on the $1 bill and the quarter, Thomas Jefferson on the $2 bill and the nickel, and Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill. Alexander Hamilton, the Hamilton musical hero and first secretary of the treasury celebrated on the $10 bill, bought and sold slaves for his in-laws, and Benjamin Franklin, whose face adorns the $100 bill and is perhaps the most highly esteemed founding father after George Washington, owned seven slaves.

“For many of my students, the very thing they’re promised will give them a better life—money—reflects the story of American imperialism and oppression,” Bret Turner, an Oakland, California, first-grade teacher, wrote in an article for the Southern Poverty Law Center’s newsletter in 2019. Proposed legislation in Congress calls for former slave and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman, who is credited with leading hundreds of slaves to freedom, to replace Jackson on the $20 bill. If she ever gets her currency close-up, she’ll be the first Black woman to do so.

Wall Street

A symbolic representative of U.S. economic supremacy, Wall Street is not without its own troubling slavery connection. Just two blocks away from the New York Stock Exchange was one of the largest slave markets in the country, and enslaved people actually built the wall for which Wall Street was named. Ties to the institution of slavery go beyond Wall Street as well. In 1817 New York became the first state to enact a law completely abolishing slavery (it went into effect in 1827), but the state continued to earn revenue from cotton picked by unpaid slave labor.

The insurance industry

While U.S. banks financed the survival of Southern plantation owners, insurance companies like New York Life, Aetna and US Life sold insurance policies to owners of enslaved people. These policies protected against the loss of slaves on transatlantic trips to the United States and as a result of dangerous labor in mines, lumber mills and turpentine factories. According to the New York Times, more than 40 other companies offered such policies to Southern slave owners, though most of them have long since ceased operations.

In 2000, Aetna offered “deep regret” for its involvement in the slave trade, and Lloyd’s of London apologized for its role in an “appalling and shameful period of English history” in a 2020 statement, pledging financial support to charity organizations for Blacks and other minority groups. New York Life, whose predecessor, Nautilus Mutual Life Insurance, sold slave life insurance policies between 1846 and 1848, acknowledges its slavery connection on its website: “While we recognize that we cannot change our company’s past, our understanding of those two years of our history has played a role in our long-standing commitment to diversity and inclusion, and our dedication to uplifting the Black community, both within our company and in the communities we serve.”

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We’ve gone the extra step and had Ambrose Martos, a fact-checker with 20-plus years of experience researching for national publications including National Geographic Adventure and Popular Mechanics, verify that all facts, studies and quotes are correct. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.

Sources:

- New Haven Independent: “Yale Must Change Its Name”

- NPR: “Should Statues Of Historic Figures With Complicated Pasts Be Taken Down?”

- Time: “Michelle Obama Reminded Us That Slaves Built the White House. Here’s What to Know”

- Architect of the Capitol: “Philip Reid and the Statue of Freedom”

- PolitiFact: “The legend of slaves building Capitol is correct”

- New York Life: “Acknowledging our past: New York Life and slavery”

- Smithsonian Magazine: “Retracing Slavery’s Trail of Tears”

- VestOJ: “A Stain on an All-American Brand”

- PBS: “Citizen Ben”

- Southern Poverty Law Center: “Open Secrets in First-Grade Math: Teaching About White Supremacy on American Currency”

- BBC: “The hidden links between slavery and Wall Street”

- New York Times: “Insurance Policies on Slaves: New York Life’s Complicated Past”